In a previous post, I compared the two most widely used Hebrew lexicons, BDB and HALOT. Now, I want to do the same thing for Greek lexicons. The question to answer this time is If I’m using Thayer, should I get BDAG? This may sound like a nonsensical, no-brainer question to some. But there are plenty of pastors who still use Thayer as their go-to lexicon. The target audience of this comparison is the average user. Remember, no black belt lexicology going on here.

Thayer refers to Thayer’s Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament by Joseph H. Thayer. This is the earlier work, published in 1889, and the cheaper (even free). BDAG is short for A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, 3rd Edition. The letters in BDAG are the initials of the four lexicographers behind the work: Bauer, Danker, Arndt, and Gingrich. BDAG is the newer work, published in 2001, and the more expensive.

We’re going four rounds this time. These words come from Colossians 3:20–21. And for each, I’ll provide a verse in English with the word in bold that we can check against Thayer and BDAG. Again, I’m using digital versions of these resources. (I own all of my lexicons in print, but I enjoy the ability to access most of them using Accordance Bible Software.) Let’s begin.

Round 1: ὑπακούω

Col 3:20 Children, obey your parents in everything, for this pleases the Lord.

All screenshots in this post are from Accordance Bible Software.

BDAG: This is a long one. BDAG begins by offering forms of this verb we can expect to find in the NT. We’re referred to the related term ὑπακοή (glossed as obedience and answer) for further lexical investigation. Then there is a whole slew of attestations of this word where we can find it outside of the NT. These are nice to have, but probably not ones we’re going to consult for basic exegesis (except for hopefully the LXX). And now we get to the senses. BDAG gives us three, and Col. 3:20 is listed under the first. There’s a short definition: “to follow instructions,” and three glosses: obey, follow, be subject to. There’s a grammatical distinction between the use of this word with a dative of person and a genitive of person. Our word in Colossians is part of the rarer dative variety. There’s a reference to BDF we can chase down for further investigation, and at the end of the entry, we’re referred to Moulton and Milligan’s Vocabulary of the Greek New Testament (M-M).

Thayer: Thayer offers a transliteration and a couple of tense forms (transliterated only). As far as attestation goes, it just says “from Herodotus down.” Then there’s a gloss (to listen, hearken) followed by two senses. Colossians 3:20 is classified under the second sense: “to hearken to a command, i.e. to obey, be obedient, submit to.” And then there’s a grammatical note that this usage involves a dative of person, rather than a genitive.

Evaluation: Even though we’re not going to check all the bibliographic data, it does bolster my trust in BDAG to know a lot is going on under the hood. Thayer’s “from Herodotus down” doesn’t do much for me. BDAG gives us a short definition with glosses; Thayer only glosses. Both sets of glosses are similar enough, but Thayer’s hearken is archaic. Both resources distinguish between the dative and genitive construction. BDAG also helpfully points us to a Greek grammar and another lexical resource. I’m no fan of Thayer’s propensity to transliterate, but, to be fair, those who cannot read Greek might see this as a benefit. The win for this round goes to BDAG due to its contemporary glosses and superior bibliographic data.

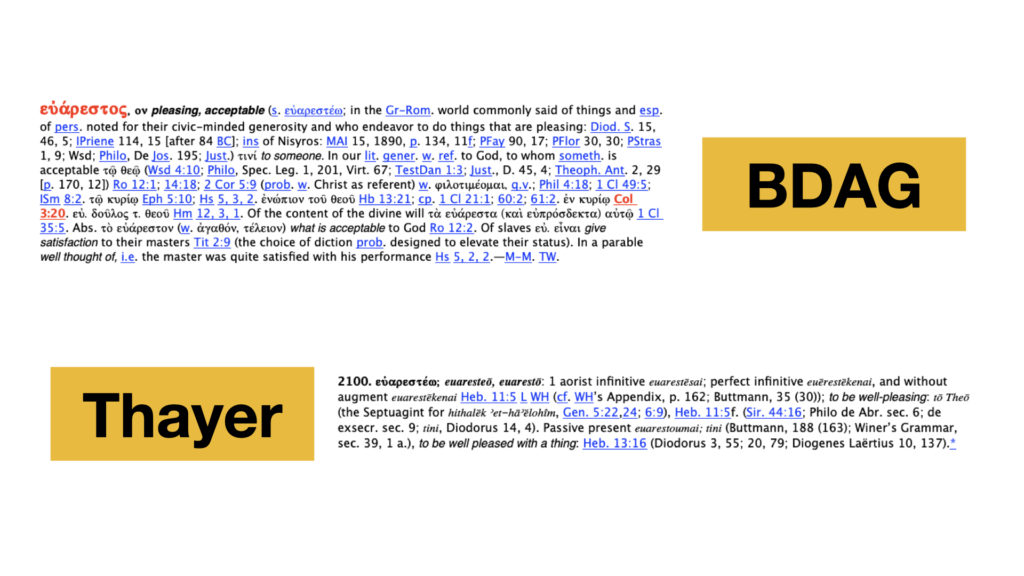

Round 2: εὐάρεστος

Col. 3:20 Children, obey your parents in everything, for this pleases the Lord.

BDAG: Again, there’s some bibliographic data as is the case for all of these entries in BDAG. There are two glosses: pleasing and acceptable. There’s some background on how this term was used in both Greco-Roman culture and Scripture. And we find Col. 3:20 is a passage where the word is used in reference to God. For the finishing touch, it’s always good to know we can check Moulton and Milligan (M-M) for additional lexical data.

Thayer: There’s some etymology followed by two glosses. This word joins εὖ (well) with ἀρεστός (pleasing). The two glosses are well-pleasing, acceptable. Thayer gives us all the NT occurrences. And we see this word shows up with the preposition ἐν in Col. 3:20. Thayer then directs us to the entry for ἐν if we want to study the significance of that construction further. Lastly, we’re referred to the next entry for more data—the adverb εὐαρέστως (in a manner well-pleasing to one, acceptably).

Evaluation: The contextual background from BDAG is helpful. We only have glosses to compare as there’s no definition in BDAG. Is there a significant difference between pleasing and well-pleasing? I don’t know. BDAG and Thayer both gloss the related term ἀρεστός as pleasing. It would be nice to have a little more, but I’ll give BDAG the win because of the contextual explanation of how this term was used in Greco-Roman culture.

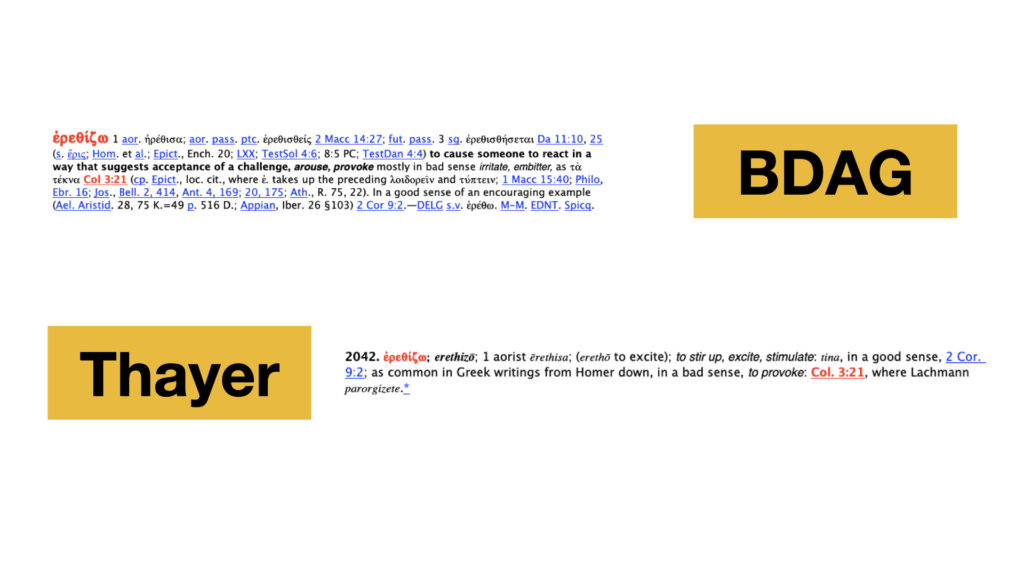

Round 3: ἐρεθίζω

Col. 3:21 Fathers, do not provoke your children, lest they become discouraged.

BDAG: This entry is short and sweet. We have three verb forms and bibliographic data. We have a definition: “to cause someone to react in a way that suggests acceptance of a challenge.” We have two glosses: arouse and provoke. And there’s some further clarification: “mostly in a bad sense, irritate, embitter,” as is the case here in Col. 3:20. And, this time, the finishing touch includes reference to three first-rate lexical works for further study: M-M, Exegetical Dictionary of the New Testament (EDNT), and Spicq’s Theological Lexicon of the New Testament.

Thayer: We have just one verb form. And the only bibliographic data we get is the vague “common in Greek writings from Homer down.” There’s an etymological note that this word is derived from ἐρέθω (to excite). Thayer then tells us ἐρεθίζω can be used in a good sense, such as in 2 Cor. 9:2, or in a bad sense, such as in Col. 3:21. Then we have the gloss to provoke, followed by a text-critical note on a variant reading.

Evaluation: BDAG knocks Thayer flat in this round. Thayer only gives us the gloss provoke and tells us Col. 3:21 uses it in a “bad sense.” The word provoke doesn’t give us much to go on for interpreting this passage. BDAG offers much more with a helpful definition and several glosses, not to mention references for further study.

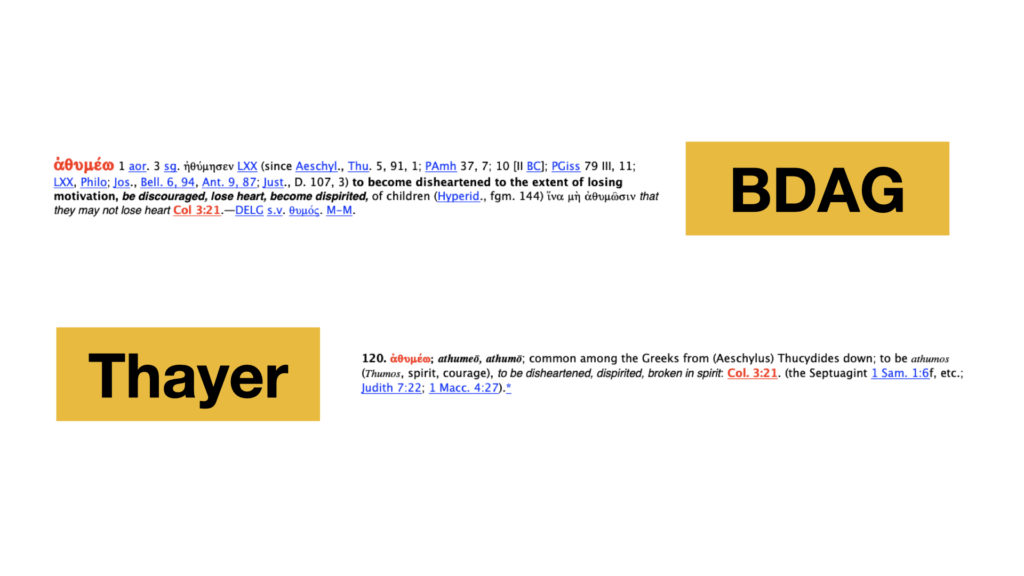

Round 4: ἀθυμέω

Col. 3:21 Fathers, do not provoke your children, lest they become discouraged.

BDAG: They don’t get much shorter than this—definition, three glosses, and a note that it’s used in reference to children in Col. 3:21 with a little context. Here are the definition and glosses: “to become disheartened to the extent of losing motivation, be discouraged, lose heart, become dispirited.” Other than that, if you want to see additional examples of usage, you could start with the Septuagint (LXX). And we might be tempted to check Hyperides (Hyperid.), who used this term in a context with children. Unfortunately, if you do decide to go down that path, you’ll find little exegetical payoff. But I’ll save that exploration for a future blog post. (If you want to tackle fragment 144, it’s available here.)

Thayer: Thayer follows suit with a short entry, He begins by telling us this was a common word starting with Aeschylus (c. 523–456 BC) and Thucydides (c. 460–400 BC). The etymological root is θυμός, glossed here as courage and spirit. (It’s worth noting that BDAG glosses θυμός as passion and wrath.) There’s no definition given, but there are three glosses: to be disheartened, dispirited, broken in spirit. We’re given every reference where this word occurs in the NT (indicated with an *), and there are a few references where we can find this word in the LXX.

Evaluation: It’s probably no surprise that I’m handing the win to BDAG. The glosses from both resources are fairly comparable. Yet again, Thayer’s terminology shows some age. And I particularly like how BDAG gives us an actual definition. When it comes to attestations outside of the NT, both resources point us to the LXX. Only BDAG offers the brave student an enticing reference that would appear to be a parallel usage involving children. (There is actually more going on in Hyperides than meets the eye. And BDAG’s use of this reference is something I plan to explore in a future blog post.)

Conclusion

I see why pastors use Thayer. It’s cheap or free depending on how you access it. You can look up terms with Strong’s numbers and there are transliterations, making it more accessible for those who don’t know Greek. Plus, you get some etymology, and pastor’s love to preach some etymology. That being said, etymology can be dangerous unless you really know what you’re doing. So I would say the average user is better off without it. From this brief comparison, we see that BDAG is well-researched, up-to-date, and often provides definitions rather than merely glosses. The clear win across the board goes to BDAG.

Let me know if you found this helpful. Next, I’ll begin a three-part series comparing HALOT and the Dictionary of Classical Hebrew.

Thanks to Duncan Johnson and evagre from the subreddit r/AncientGreek for their help on the Hyperides citation!

Recommended Reading for Further Study

Exegetical Fallacies by D. A. Carson

A History of New Testament Lexicography by John A. L. Lee

Linguistics and Biblical Exegesis by Douglas Mangum and Josh Wesbury (eds.)

These are helpful comparisons. Thank you! What you might also consider comparing is BDAG with the Exegetical Dictionary of the New Testament. It’s not exactly a lexicon, but for NT word study, I recommend it to my students as often being more helpful. Words are organized by root, so, e.g., the entry on υπακουω is connected with υπακοη. The entry is quite long. As an example, here is the entry for εὐάρεστος you cited. As you can see, it doesn’t give as much grammatical or classical information, but it comments on all the NT usages.

εὐάρεστος, 2 euarestos pleasing, pleasant*

There are 9 occurrences in the NT, of which 5 are in Paul. The word is widespread in koine, but rare in the LXX (only in Wis 4:10; 9:10). In the NT it is used almost exclusively of deeds that are pleasing to God or Christ: Rom 12:1: εὐάρεστον τῷ θεῷ, of the living and holy sacrifices of the bodies of believers (cf. δόκιμος τοῖς ἀνθρώποις, 14:18); further Phil 4:18; 2 Cor 5:9 (εὐάρεστοι αὐτῷ); Eph 5:10; Col 3:20 (εὐάρεστον ἐν κυρίῷ); Heb 13:21 (εὐάρεστον ἐνώπιον αὐτοῦ); absolute τὸ ἀγαθὸν καὶ εὐάρεστον καὶ τέλειον as content of the will of God, Rom 12:2. According to Titus 2:9 slaves are to conduct themselves in a way that is pleasing to their masters. Εὐάρεστον is a comprehensive fundamental term in parenetic language involving the believer’s task of examining the will of God in one’s particular situation. W. Foerster, TDNT I, 456f.; H. Bietenhard, DNTT II, 814–17.

Mark, thanks for the comment! EDNT is an excellent resource, and one I ,also, use regularly. Thanks for pointing out its value. In addition to your suggestion, others have recommended BDAG vs. BrillDAG (GE) and an assessment of Trench’s Synonyms. Another one I would like to do is Muraoka’s A Greek-English Lexicon of the Septuagint vs. LEH. But, first, I need to tackle HALOT vs. DCH. Plenty to keep me busy in my free time!

Yes, BDAG vs. BrillDAG would be interesting indeed! I’ve not had a chance to look much at Muraoka, but LEH isn’t much more than a gloss. The other comparison would be the Danker Concise (which I don’t have) vs. BDAG.

Yes, plenty to keep you busy! Thanks again.

The only advantage that I’ve seen from Thayer is often he will give corresponding synonyms and antonyms in some of his entries which BDAG. does not do. I would also be interested in knowing if you plan on doing a comparison between Thayer and Abbot-Smith.

Agreed on Thayer. I can see some use for that data. Abbot-Smith also gives some great data like synonyms and Hebrew renderings from the LXX. You know, covering Abbot-Smith is a great idea. Do you think Thayer is its closest competitor?

Great comparison between the two, and I would certainly support your conclusion. Would there be any situations where you would say that Thayer’s would be a better go-to source, assuming I own both? Would Louw-Nida figure into your consideration?

Jeremy, the only potential areas of value I see in Thayer are the transliterations and etymology. I do like how Thayer includes an asterisk when every NT occurrence of the word is included under the entry. BDAG doesn’t do this.

I’m a big L&N fan. It’s a great lexicon to use alongside BDAG for its methodological priority of definitions over glosses. It’s also handy to be able to consider your words within their semantic domain.

Great! Thank you.