An Introduction and Review of the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae (TLG)

The Thesaurus Linguae Graecae, hereafter abbreviated TLG, is the premier online database of Greek literature. According to the TLG website,

The TLG® Digital Library contains virtually all Greek texts surviving from the period between Homer (8 c. B.C.) and the fall of Byzantium in A.D. 1453 and a large number of texts up to the 20th century. The TLG corpus is available in more than 2,000 universities and research centers around the world and used by thousands of researchers, educators, and students from a wide range of disciplines such as classics, archaeology, history, art, history, philosophy, linguistics, and theology/religious studies. [1]

For many years, my only exposure to the TLG was footnote references and enigmatic references in monographs and journal articles. From my own experience and personal impressions, the TLG is largely ignored in most Bible college and seminary programs. Yet the TLG is not only for advanced scholars. Studying a large corpus of Greek literature allows us to better understand the Greek language, which can yield dividends for studying the Greek New Testament. Therefore, students should receive some training or at least exposure to this important tool.

I am a PhD candidate working in biblical studies and my interests include linguistics and theology/religious studies. My review of the TLG will emphasize points I believe will most interest people doing similar work. The outline of my review will follow the features of the TLG: Canon, Text Search, Browse, Lexica, N-Grams, Statistics, Vocabulary Tools, and Help.

Search the TLG Canon

This feature allows you to search for a work within the TLG canon by . . .

- Author

- Editor

- Work Title

- Publication Title

- Series

- Publication Year

Helpfully, the Canon Search offers auto-complete, so you do not necessarily have to type out your entry in full, which comes in handy if you can’t remember how to spell a name like “Aeschines Socraticus” or “Ptochoprodromica.” Note that many of these works are found under their Latin title. For example, to search the New Testament, you will need to select “Novum Testamentum.” Locating the Apostolic Fathers could be a little more difficult. In this case, it was easier to search by Publication Title for “Die apostolischen Väter.”

If you’re looking for a specific author or work, this is the place to go. By clicking “Complete author list,” you can also browse every author in the TLG alphabetically or by date range. This component is actually open access and can be accessed here without an account or subscription.

Searching the canon is a useful means of pulling up an entire work. The TLG contains over 10,000 works by 4,000 authors, giving you access to an incredibly large corpus.

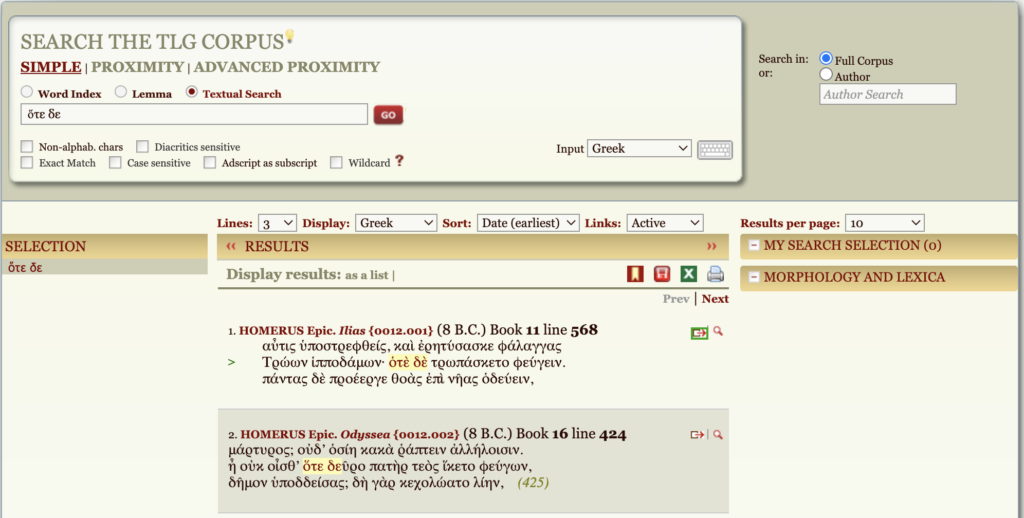

Search the TLG Corpus

You can perform three types of searches: simple, proximity, and advanced proximity. You can also specify whether you want to search by word index, lemma, or textual search. I was interested in looking at the phrase “ὅτε δε” for a project I was working on, so I ran a simple textual search. The TLG does not provide a total number of search results when you search for a string of words, but scrolling down through the results for ὅτε δε, I found that there were 6,748. (The Digital Loeb Classical Library, by comparison, contains approximately 650 occurrences.) If I sort results by date, I find that the earliest occurrences in the TLG corpus come from Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey.

You can perform more advanced searches using the Advanced Proximity search option, which allows you to include grammatical categories in your search. This feature is currently in the beta release stage, and as the help file warns, may produce spurious results because of the ambiguity of certain wordforms.[2]

As a test, I wanted to see examples predating the composition of New Testament in which someone is said to die (ἀποθνῄσκω) for (ὑπέρ) someone else (for my search, a genitive pronoun). I made the following selections for an Advanced Proximity search:

Box 1

Lemma: ἀποθνῄσκω / Within 3 words

Box 2

Lemma: ὑπέρ / after first word

Box 3

Grammatical Category: Pronoun / Genitive / after first word

The TLG returned seven results before any New Testament results, with the first result dated to the fifth century BC. (I have omitted duplicates and any results in which search words appear in separate sentences or clauses.) For many works, the TLG offers a link to a translation, but this is not always the case. I have included these translations, as applicable, below.

1. Critias, Testimonia (1st century BC)

ἐμοὶ δὲ ἀποπεφάνθω μηδένα ἀνθρώπων καλῶς δὴ ἀποθανεῖν, ὑπὲρ ὧν οὐκ ὀρθῶς εἵλετο.

But let it be declared on my part that none among men died well for a poor choice.[3]

5. Hyperides, Against Demosthenes (4th century BC)

οὕτως οὖν ἡμῖν τοῦ δήμου προσενηνε γμένου, οὐ πάντα <τὰ> δί[κ̣α]ι̣ ἂ̣ν̣ αὐτῷ ἡμεῖς ὑπ̣η̣]ρετοῖμεν καὶ εἰ δ[έοι ἀ]π̣οθνῄσκοι μεν [ὑπὲρ] α̣ὐτοῦ;

When the people have acted thus towards us should we not render them all due service, and if need be die for them?[4]

6. Lycurgus, Against Leocrates (4th century BC)

ἆρά γ’ ὁμοίως ἐφίλουν τὴν πατρίδα Λεωκράτει οἱ τότε βασιλεύοντες, οἵ γε προῃροῦντο τοὺς πολεμίους ἐξαπατῶντες ἀποθνῄσκειν ὑπὲρ αὐτῆς καὶ τὴν ἰδίαν ψυχὴν ἀντὶ τῆς κοινῆς σωτηρίας ἀντικαταλλάττεσθαι;

Is there any resemblance between Leocrates’ love for his country and the love of those ancient kings who preferred to die for her and outwit the foe, giving their own life in exchange for the people’s safety?[5]

7. Strabo, Geography (1st century BC–AD 1st century)

καὶ τὸ κατασπένδειν αὑτοὺς οἷς ἂν προσθῶνται, ὥστε ἀποθνήσκειν αὐτοὺς ὑπὲρ αὐτῶν.

And it is an Iberian custom, too, to devote their lives to whomever they attach themselves, even to the point of dying for them.[6]

As a result of my search, I was able to identify examples not found in the Loeb Classical Library, Searching the TLG is also extremely easy. You will want to refine your search criteria as much as possible to limit your results. The lack of English translations may also slow down some users who wish to quickly examine a large number of texts.

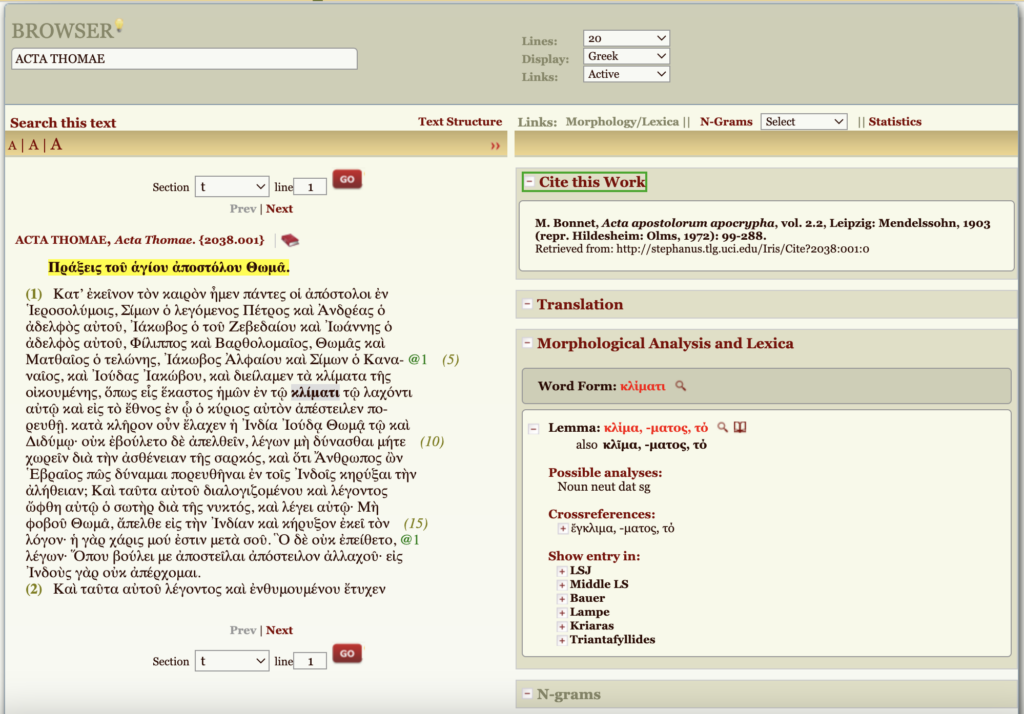

Browser

The browser gives the user two options: “Browse One Text” or “Parallel Browsing.” After selecting a work, the TLG displays the text for you to read. You also have immediate access to bibliographic information for your chosen text, translations, morphological analysis, and links to lexicons.

Translations are not available for every text, and when a translation is available, the TLG directs you offsite to websites such as Perseus or, as I found in the case of Clement of Alexandria’s works, New Advent. The morphological tagging seems accurate. Performing a brief test by checking the TLG’s tagging of Psalm 22 (LXX), I did not identify any inaccuracies.

While the morphological analysis appears whenever you click a word, you will have to view lexical entries in a separate tab. Note that the TLG does not typically provide lexical glosses that users of Bible software might be accustomed to, although I did notice that glosses occasionally appear under the “Lemma” heading.

Parallel Browsing is a nice feature that allows you to compare separate editions of the same work, when applicable, or compare two different texts to identify shared wording and similarities.

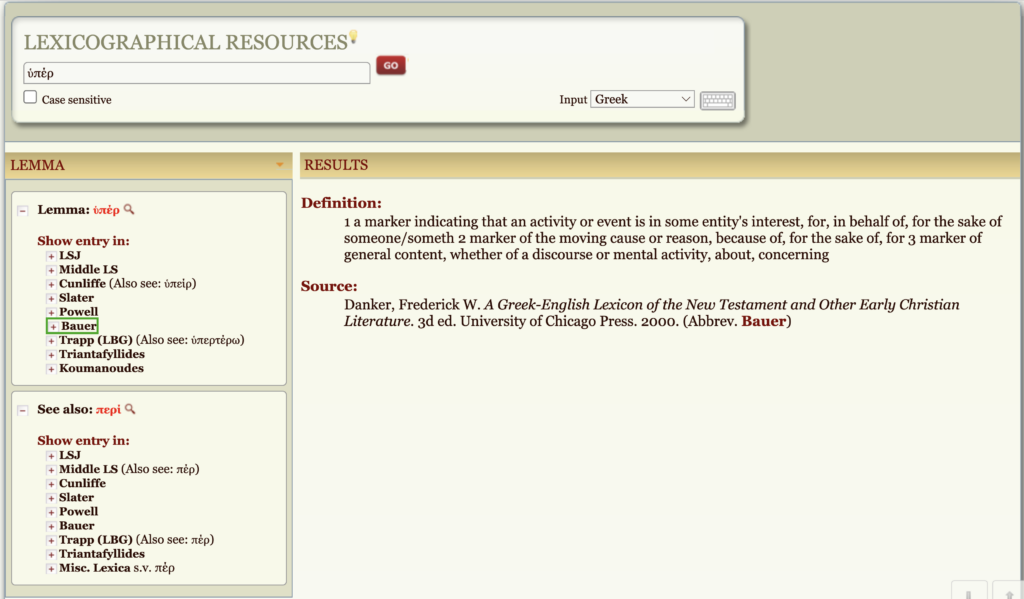

Lexicographical Resources

Using this tool, you can quickly consult an array of lexicons for a given word. For example, my search for ὑπέρ gives me access to the following at the click of a button:

- Liddell-Scott-Jones, Greek-English Lexicon (LSJ)

- Liddel and Scott, An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon

- Cunliffe, A Lexicon of the Homeric Dialect

- Slater, Lexicon to Pindar

- Powell, A Lexicon to Herodotus

- BDAG

- Trapp, Lexikon zur byzantinischen Gräzität

- Kriantafyllides, Dictionary of Standard Modern Greek

- Koumanoudes, Synagoge

Depending on the word, the TLG will also return results from Diccionario Griego-Español, Lampe’s Patristic Greek Lexicon, Kriaras’s Lexicon of Medieval Greek Demotic Literature, Triantafyllides’s Dictionary of Standard Modern Greek, and others.

Some of these will be more useful than others, depending on your line of inquiry. This feature allows you quick access to useful resources such as LSJ, Cunliffe, Powell, and Lampe, but you will probably want to access BDAG via other means because TLG only provides the definitions for a word.

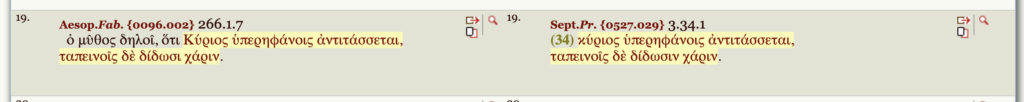

Intertextual Phrase Matching (N-Grams)

The TLG defines an N-gram as “overlapping sequences of content words in the text.” This tool allows you to identify texts that share similar wording. Note that an N-gram search allows you to constrain your search to matching wordforms or to expand your search to uninflected lemmas. You can also adjust the minimum number of matching words you want the TLG to require for search results.

The N-gram search creates all kinds of possibilities because you can identify borrowing between different texts and authors. I wanted to compare Aesop’s Fables with both the New Testament and Septuagint, and look what I found:

Proverbs 3:34 (LXX) and Aesop’s “Two Roosters and the Eagle” have a textual relationship. In this fable, two roosters first fight over a hen. The defeated rooster retreats, the victorious rooster crows in triumph, and an eagle swoops down and snags the jubilant rooster. In the end, the rooster who lost the fight gets the hens. But note the epimythium:

ὁ μῦθος δηλοῖ, ὅτι Κύριος ὑπερηφάνοις ἀντιτάσσεται, ταπεινοῖς δὲ δίδωσι χάριν.

The tale shows that the Lord opposes the proud, but gives grace to the humble.

That’s a quotation from Proverbs, and wording that also appears in the New Testament (Jas. 4:16 and 1 Pet. 5:5). The editors of Corpus Fabularam Aesopicarum note in a footnote that. according to Adamantios Korais, a later Christian author inserted this concluding moral.

The N-gram search allows you to compare any two texts, giving the user countless opportunities to discover fascinating connections between texts. Compare the New Testament against the works of John Chrysostom or Eusebius. Compare the Septuagint against Plutarch, Josephus, or the Life of Adam and Eve. You can also allow the TLG to search for N-grams within the browser and identify shared wording between any text within the entire corpus.

Statistics

This tool gives you access to statistics for the entire TLG corpus, an individual author, work, or usage of a word. What kind of stats? In addition to a summary, the TLG gives you . . .

- Most Frequent Wordforms

- Most Frequent Lemmata

- Most Over-Represented Lemmata

- Most Under-Represented Lemmata

- Unique Occurrences (~hapaxes)

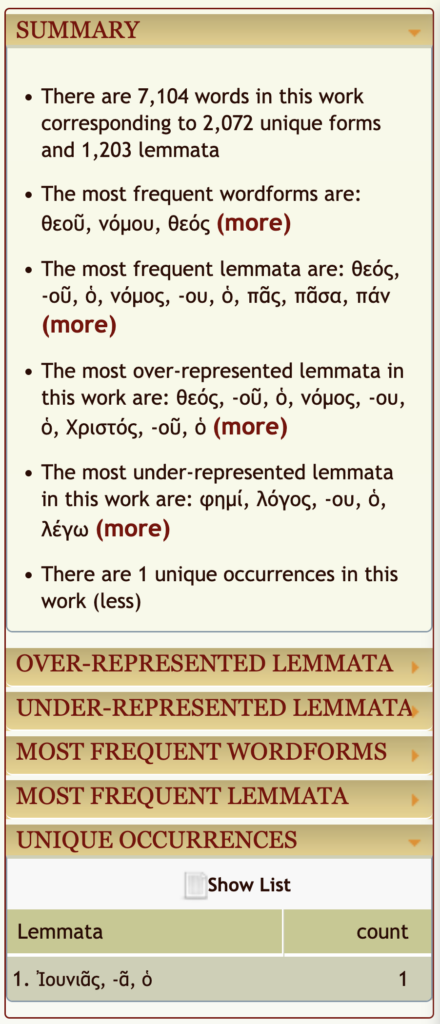

If we select the book of Romans within the work of “Novum Testamentum,” the TLG provides this summary:

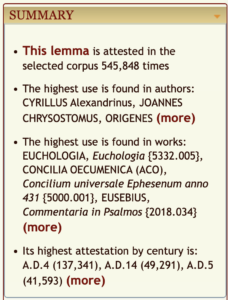

If you want to see statistics on θεός, one of the most frequent lemmas appearing in Romans, you get information like this:

This tool could prove helpful in all kinds of ways, whether you want to know more about an author’s style or dig deeper into how a word appears throughout the corpus.

Vocabulary Tools

The Vocabulary Tools page allows you to generate a vocabulary list for a given author or work. You can then view these vocab words in a flashcard format on your screen.

Help

The TLG can look intimidating at first glance, but the help files, frequently asked questions page, and video tutorials will answer almost anything you want to know. Should you require any further assistance, you can email the TLG team directly or fill out the form on the main page.

I found the help files extremely useful. These are PDF slides with images and explanations of how to use each feature. At present, there are four short yet informative video tutorials currently available. These cover . . .

- The TLF Canon of Greek Authors and Works (6:57 in length)

- Introduction to the TLG Text Search (8:13 in length)

- Browse One Text (3:07 in length)

- Parallel Browsing (2:41 in length)

The TLG is fairly intuitive in and of itself, but I was able to easily access the help files and find the answers to all my questions. What was most helpful to me was being able to click the lightbulb icon next to the heading for a given tool, which provides instant access to the help files in a separate browser tab.

Conclusion

No other resource can compete with the TLG if you want to conduct serious research on the Greek language. The size of the corpus is massive and still growing. Works are added regularly with 88 new works just added in September. You can quickly conduct powerful searches and easily access morphological and lexical information. No other resource allows you to search such a large corpus, be it Perseus, the Loeb Classical Library, or your personal Bible software package.

Are there any other specific considerations that those working in biblical studies might want to know about? I can think of four.

First, the editions of some texts biblical scholars might consult are dated. For example, the Greek New Testament text is that of UBS2, 1968. The Acts of John text is that of Bonnet (1898), and not that of Junod and Kaestli (1983). But differences in wording between older and new editions will be, for the most part, slight.

Second, the authors and titles of works are in Latin. It might take a few extra seconds to find CLEMENS ALEXANDRINUS, BARNABAE EPISTULA, JOSEPHUS ET ASENETH, and TESTAMENTA XII PATRIARCHARUM. The Latin names for these and many others are close enough to make searching and browsing, in most cases, a generally straightforward matter. Although, I would prefer if users could search for works by their English title.

Third, the availability of English translations is limited. For instance, there is no English translation available for the Acts of John, the Letter of Aristeas, Aspasius’s Commentaries on Nichomachean Ethics, or Galen’s “Advice for an Epileptic Boy.” But there are links to translations for many texts. I checked several, somewhat at random, and found translations for works of Demosthenes, Diodorus Siculus, Diogenes Laertius, Plato, Plutarch, Polybius, Thucydides, and Xenophon, to name just a few. In many cases, users should be able to track down translations the TLG does not supply.

Fourth, the TLG costs money. TLG offers subscriptions to both institutions and individuals. The current cost for an individual annual subscription is $140.00. But the good news is that you also have the option to create an account to freely access the Abridged TLG, which features fewer Greek texts and features. You can create an account here.

In sum, the TLG is an amazing tool that students and scholars can benefit from. It provides ready access to a wealth of searchable texts that can help us better understand Ancient Greek. The advanced proximity search affords users the capability to perform specific grammatical searches. If you are a scholar or student working in biblical studies, you will find the TLG to be an excellent resource for researching the Greek language.

You can visit the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae here.

Special thanks to Maria Pantelia and Thesaurus Linguae Graecae for granting me account access in exchange for an honest review. This did not affect my thoughts in any way, so far as I know.

Very helpful. I have been overwhelmed when trying this out.

Thanks so much, Jeff!

I appreciate your reviews and this one is a great example of something I am curious about but didn’t know how to investigate.

Thank you, Nick! I appreciate you reading the review I share.